3 How do we love?

Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

Matthew 22:37-40

If we put aside the categories and logic of Greek philosophy and try to understand biblical religion in its own terms, we will soon discover that the God of the bible is not Aristotle’s impassive, unmoved mover at all; he can only be described as “the Most Moved Mover.” … According to the Bible, the single most important thing about God is not his perfection but his concern for the world.

Abraham Heschell

3.1 Love thinking over rule thinking

Our [Western thinkers] confidence in a stable and orderly universe leads us to prioritize rules over relationships, but it does more than that. The western commitment to rules and laws make it difficult for us to imagine a valid rule to which there may be valid exceptions. When we begin to think of the world in terms of relationships instead of rules, however, we must acknowledge that things are never so neat and orderly and that rules are not as dependable as we once imagined. When relationships are the norming factor in the cosmos, we should expect exceptions. (Pg. 166)

Grace and faith are relationship markers and not forensic decrees. Paul used these terms to define a relationship, not to explain a contract or a court ruling. Likewise, holiness is a relational and not a forensic term. Imagine a wedding ceremony in which the groom vowed, “I will kiss you twice daily, with one kiss lasting at least two seconds. I will make at least one statement implying thoughtfulness every morning. I will provide three hugs per week of medium snugness, lasting three seconds…” Such a vow does not arouse love. Rules never do. While a loving husband may perform all those actions, they are the results of the relationship, not the rules that establish it.

Our tendency to emphasize rules over relationships and correctness over community means that we are often willing to sacrifice relationships on the altar of rules. … In fact, it often seems as if God is sovereign over everything except his rules. (Pg. 173-174)

Our Western worldview dislikes an image of the Christian life that implies there are different rules for me and for you. The very wording — “different rules for me and for you” — rings of basic unfairness. For wealthy and self-righteous would-be disciples, Jesus pointed out the exacting requirements for righteous living (Luke 18:18-23), but to those weary of sin he called his way “easy” and “light” (Matthew 11:30). Jesus required one disciple to sell everything to follow him (Matthew 19:21), yet he apparently hadn’t required Peter to do so (John 21). He asked one disciple to leave his family (Matthew 8:21-22), but apparently he did not make the same request of Lazarus, Mary and Martha (John 11). It seems that rules applied, except when they didn’t (Pg. 170).

3.2 Love in community

If the church is to be the witness God calls us to be, we must be ruthlessly honest with ourselves about the areas in which we are not where God wants us to be. And it is painfully obvious that one central area in which we are not remotely close to where God wants us to be is in our relationships with one another. Because of the pervasive, individualistic mindset of Western culture, modern Western Christians tend to view their relationship with God strictly as an individual thing. Church is usually thought of as a weekly, large-group gathering of believers who are for the most part strangers to one another. Even worse, we tend to identify the church as a building that simply houses individual Christians once a week for worship.

the primary building blocks for the corporate temple of God (Eph. 2:21-22) are covenantal relationships in which believers know one another profoundly, love one another deeply, and care for one another unconditionally. Only in this way do we grow in Christ and display the social love of the triune God.

In whom all the building fitly framed together groweth unto an holy temple in the Lord: In whom ye also are builded together for an habitation of God through the Spirit.

(Eph. 2:21-22)

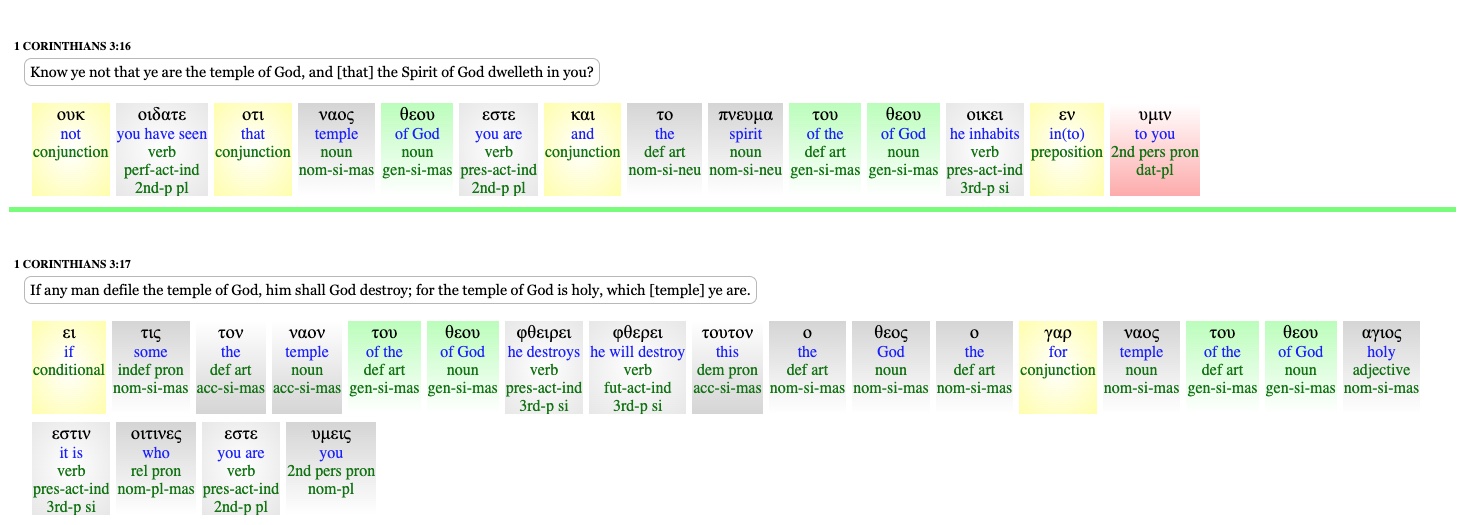

Know ye not that [you all] are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwelleth in you [all]? If any man defile the temple of God, him shall God destroy; for the temple of God is holy, which temple [you all] are.

(1 Cor. 3:16-17)

Too often, we read ‘ye are the temple of God’ as individualistic, and we then think about the ‘sins’ like defaming our bodies or struggling with personal ‘impure’ thoughts. We start to reason that the ‘Spirit of God’ can’t be with us because of our ‘sins’ as individuals. However, the verses above imply that the spirit dwells in a community. When we defile the community of God, we lose His spirit. Sin is bound and defined in terms of relationships to God’s community and the relationship of this community to God. We see love as a community-based idea. Thus, sin is antagonism to this love in community. Remember Christ’s words in Matthew 22:37-40 imply that there is really one commandment – Love. As the second is “like unto” the first.

Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

3.3 Can we understand the love of God?

In contrast to the belief that God is an incomprehensible and unknowable mystery is the truth that the nature of God and our relationship to Him is knowable and is the key to everything else in our doctrine.

Dallin H. Oaks, April 2017

The restoration of the Gospel of Jesus Christ’s grandest revelation is that God is knowable. Stated more clearly and in the voice of Dallin Oaks, “the nature of God and our relationship to Him” is not only knowable it is the “key to everything else in our doctrine.” Too often, we have so much historical belief baggage that we want to throw up our arms and say that much of the nature of God is a mystery. That we can rely on simple faith and not worry ourselves about God’s time or the details of how God loves. I am reminded of B.H. Robert’s famous quote around simple faith and the mysteries of God.

Mental laziness is the vice of men, especially with reference to divine things. Men seem to think that because inspiration and revelation are factors in connection with the things of God, therefore the pain and stress of mental effort are not required. Men raise all too readily the ancient bar - ‘Thus far shalt thou come, but no farther.’ Man cannot hope to understand the things of God, they plead, or penetrate those things which he has left shrouded in mystery. So men reason; and just now it is much in fashion to laud ‘the simple faith;’ which is content to believe without understanding, or even without much effort to understand. And doubtless many good people regard this course as indicative of reverence. This sort of ‘reverence’ is easily simulated and so pleasant to follow - ‘soul take thine ease’ - that without question it is very often simulated; and falls into the same category as the simulated humility couched in “I don’t know,” which so often really means ‘I don’t care, and do not intend to trouble myself to find out.’

Therefore one must not be surprised if now and again he finds those among religious teachers who give encouragement to mental laziness under the pretense of “reverence;” praise “simple faith” because they themselves would avoid the stress of thought and investigation that would be necessary in order to hold their place as leaders of a thinking people. Some would protest against investigation lest it threaten the integrity of accepted formulas of truth—which too often they confound with the truth itself, regarding the scaffolding and the building as one and the same thing.

The Seventy’s Course in Theology (Fifth Year), by B. H. Roberts

3.4 Seeing love in God?

The basic ideas in this relational agency can be identified rather easily. It arises from the conviction that love defines the very nature of God. Love is not merely an attribute or an activity of God- something God has or does-it is what God is in His very essence. Love defines God’s inner reality, and love characterizes God’s relation to all that is not God. God created the world as an expression of the love that God is, and love not only accounts for God’s decision to create a world distinct from himself, love also comes to expression in all of God’s relations to the world.1

When our view of the love of God is constricted by the logic of authoritarian power and perfection, salvation shows up as a tug of-war between our agency (expressed in works) and God’s agency (expressed in grace). Salvation, rather than being a covenant partnership with God, ends up being a zero-sum competition with God. Traditional debates about grace all tend to be variations on this same competition-based argument about who gets credit for what. Posed in this way, the question will always require some division of credit as an answer. As long as we try to divide up credit, we will end up outside of a loving relationship with God.2

Can we know and see God through the lens of love instead of power? Can we see His sensitivity, vulnerability, caring, compassion, attentiveness as the lens that defines His being not His authority to command or His power to know? If we will shift how we center our faith in God, I think quite a few principles will come into better focus. However, the effect of a God centered in love may throw a wrench in a few of our historical beliefs. Remember, that our ‘accepted formulas of truth—which too often [we] confound with the truth itself’ can leave us in a situation where we ‘regard the scaffolding and the building as one and the same thing.’3

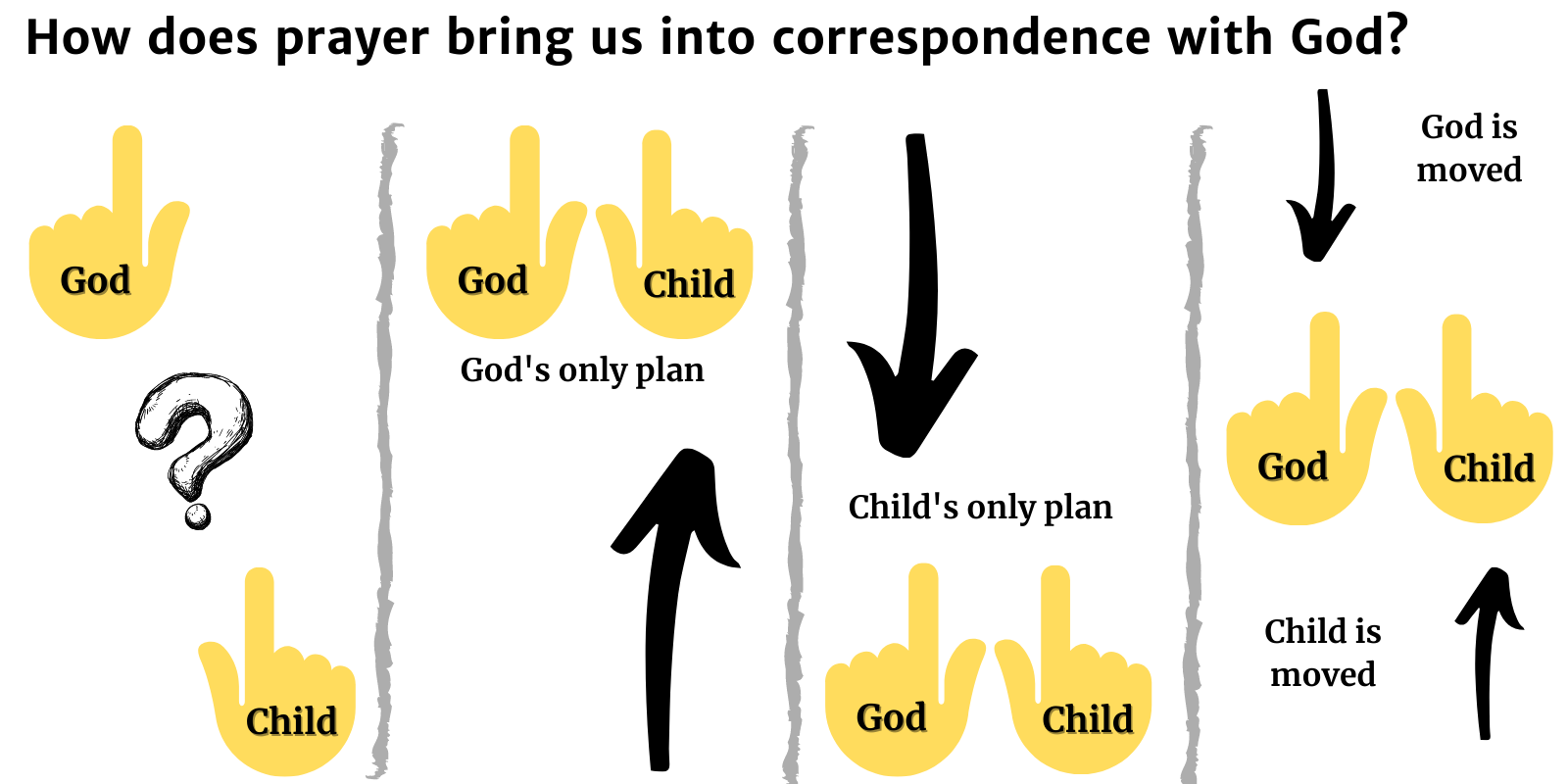

For example, when we think of God as a relational being that is defined by love it asks us to open up our view of Prayer. I have too often heard prayer described as time to bow in submission to God’s omniscience as is shared by this video from BYU Education Week a few years back.

A little into the video he shares the following quote.

The thing that’s really wrong, is we have in the attitude of prayer, the child, changing the will of the parent. In this case, a heavenly parent who knows everything. Brothers and sisters, prayer is not for us to teach God anything he doesn’t already know. Prayer is not an opportunity for me to kneel down and enlighten God on what happened in my day, or what I’m thankful for, or what I need help with. God knows all of those things infinitely better than I know them about myself. So when he commands us to pray. It’s not so that we can teach him anything. It’s so that we can learn from him. We can learn about him. And we can learn about ourselves, and we can learn about others.

The video and quote conversation focus on His omniscience and power instead of His love. Do we feel how love and relationship is placed as a secondary attribute? When have we seen any loving communication as a knowledge flex where both parties are trying to show how smart they are? He focuses on teaching God and enlightening God by our knowledge. His use of the “will of the parent” even seems to focus on changing truth instead of relationship.

His focus seems to shrink the love of God to the point where we loose out on His true desires and start to wander into false beliefs of prayer. How would God signal love and partnership with His children when we pray?

If we explained prayer through the lens of love could we see a God that “desires a deep personal relationship with us” that “requires genuine dialogue rather than monologue.”4 A relationship where both parties move as they are moved by each other. The best loving relationships don’t focus on knowledge transference or try to partition who is teaching who. The best loving relationships involve two parties joining their beliefs into one. Why would we expect anything different when we discuss our relationship with God through prayer?

3.5 Conclusion

I know that this prayer discussion may cause some cognitive dissonance. We will focus on prayer through scripture in a future chapter. At this point, I hope we start to see a vital assumption in our journey — that God is not a mythical creature beyond our comprehension. He is not an other with different and unknowable definitions of the same attributes we share with fellow mortals. As Dallin Oaks shared, “The nature of God and our relationship to Him is knowable and is the key to everything else in our doctrine.” We may fall short in our application of our knowledge or may weakly know the “nature of God and our relationship to Him” but that is a matter of degree not unique definitions for mortals and God.

A slight rewrite from The Future of Open Theism by Richard Rice.↩︎

A slight rewrite from Original Grace by Adam Miller↩︎

The Seventy’s Course in Theology (Fifth Year), by B. H. Roberts↩︎

The God Who Risks by John Sanders↩︎